Historic Educational Buildings as Community Anchors

For the 25th Anniversary of our flagship Seven to Save program, we wanted to look back with a thematic retrospective – highlighting seven themes we’ve seen pop up in our listings over the past 25 years. Over the course of the year, we’ll be digging into our STS archive to highlight places across the state that help tell a broader story of preservation in New York.

With shifts in population, budget constraints, and older buildings no longer meeting contemporary needs, many educational buildings have been vacated and left to deteriorate without an immediate new use on the horizon. In some cases, the buildings are so large that finding a new use proves difficult. In others, districts outgrow their historic buildings and move on. Regardless of particular circumstances, educational buildings tend to be local landmarks, deeply connected to a community’s identity and sense of place. People often have a strong emotional connection to these places because they (or members of their family) used them as children. Losing these places can be a major blow to a community.

If a school can no longer be a school, what can it be? In the case of both the Corning Free Academy (STS 1999) and the Dana L. Lyon School in Bath (STS 2007), the answer is housing.

When it was listed in 1999, we wrote that “the 1922 Corning Free Academy faces an uncertain future, as the school board explores plans to construct a larger, consolidated middle school.” When State funding is available to construct new schools, districts may choose to explore that option — even if it means abandoning their historic neighborhood school buildings. Corning Free Academy did eventually close for exactly that reason, but thankfully, community support laid the groundwork for a transition into an adaptive reuse project. The school held its final classes in June 2014 and by August, developer Purcell Construction Corp. and architects from Johnson-Schmidt Architect, P.C. had begun the redevelopment. Being located in Corning’s Southside Historic District meant the project was able to benefit from Historic Tax Credits, making the work more financially feasible. The rebranded Academy Place opened in 2015 with 58 apartments in a building that retained much of its historic character, including elaborate terra cotta pieces made by the Corning Brick and Terra Cotta and Tile Company, original wood floors, and decorative glass shades throughout. From an article published by The Leader following Academy Place’s ribbon cutting, president of the Southside Neighborhood Association David Dowler said, “The people that built this in 1922 could not have imagined a finer future for their building.”

The Dana L. Lyon School closed for similar reasons, but its reuse has been much more fraught. Closed since 2002, a rehabilitation is currently underway to transform the former elementary school into affordable housing. By the time the school landed on our Seven to Save list in 2007, local advocates had been fighting for four years to prevent its demolition. The League worked closely with the Save the Lyon Commission (STLC) on community advocacy, urging village leaders to not move forward with the proposed rezoning that would have resulted in its demolition. It took 10 years following the school closing, but STLC finally took ownership of the building in 2012. It took another eight years for the building to make its way into the hands of Rochester-based developer Providence Housing. Reported by WENY News in 2020, Walt Longwell of the Save the Lyon Commission said, “Transforming the Dana Lyon School building in a way that preserves its historic integrity has been our goal from the inception of our organization. We are grateful to Providence, the Village of Bath, Steuben County, our membership and legal representation, and the Steuben County IDA for their work to create this unique solution that honors the generosity of the Davenport family and helps to meet housing needs of our community.” The project team expects to finish the rehabilitation in 2025, turning the former school into 49 apartments. We look forward to seeing this former Seven to Save become officially “saved.”

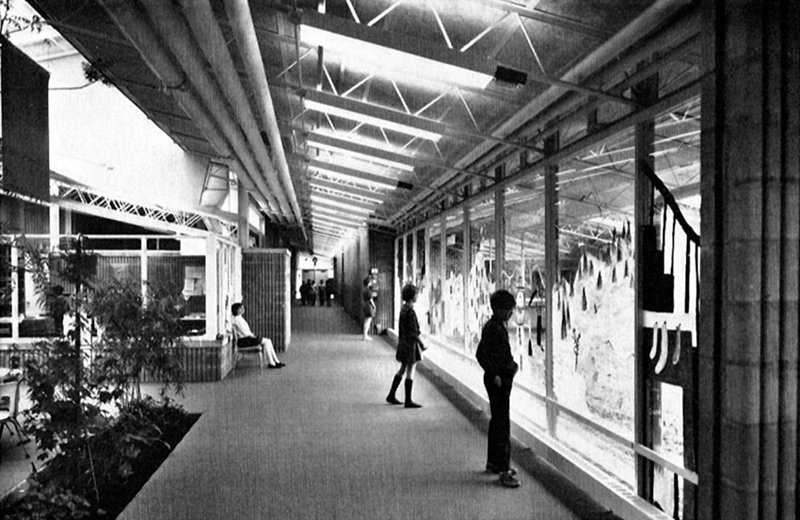

We’ve also seen incredible transformations of former school buildings into art centers. The former Niagara Falls High School (STS 2000), for example, is now The Niagara Arts and Cultural Center. Niagara Falls High School was vacated in 2000, shortly before the building landed on our Seven to Save list. As we wrote then, “Unless city government, the school board, and others can agree on the desired outcome for the building and site, the Classical Revival style school will be leveled and a shopping mall will be built in its place.” Indeed, the building was slated for demolition. Thankfully, grassroots advocates organized to save the building, making it clear to local officials that there was strong community support for reusing the former high school. After heated debates, those grassroots activists claimed a victory — in 2001, the 180,000-square foot building was transformed into the Niagara Arts and Cultural Center (NACC) and shortly after it was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The NACC is a community-focused cultural center, supporting and exhibiting artists of all disciplines and providing creative experiences for members of the public. From the Niagara Falls National Heritage Area, “the classrooms were converted into artists’ studios and the cafeteria and two other spaces were turned into public art galleries. The 8,000 square foot gymnasium was certified as a sound stage for film and television development… The library and 900-seat auditorium were converted into theaters. Outside, the balustrade main staircase became a stage for summertime jazz concerts.” Other great examples of this kind of adaptive reuse include the Jack Shainman Gallery in Kinderhook, which occupies the former Martin Van Buren High School, and The Campus in Claverack, which opened earlier this summer in the former Ockawamick School just outside Hudson.

Despite case studies from around the state of successfully reused school buildings, some vacant schools are eventually demolished (as was the case for the Paul Rudolph-designed John W. Chorley Elementary School in Middletown, STS 2010) or sit vacant, without the community support or political will to find their next chapter. A good example of this kind of “white whale” building is St. Paul’s School in Garden City (STS 2003). The National Register-listed building is in much the same situation now as it was over 20 years ago. In 2003 we wrote, “To save the building, it will be necessary to convince a broad array of community stakeholders that it is architecturally and economically feasible to reuse St. Paul’s School in ways that respect its outstanding High Victorian Gothic design.” The people of Garden City have been debating the fate of St. Paul’s ever since, most recently holding a public referendum in late 2023 asking citizens to vote either in favor of preservation or demolition — 61% voted to preserve. The League continues to support local efforts to save St. Paul’s, and there are passionate preservationists committed to finding a path forward. But without a clear consensus, the future of this Victorian masterpiece remains uncertain.